This post is part of Aid to Zen – A Quick Guide to Surviving Aid Work from A to Z by Alessandra Pigni

***

In the field

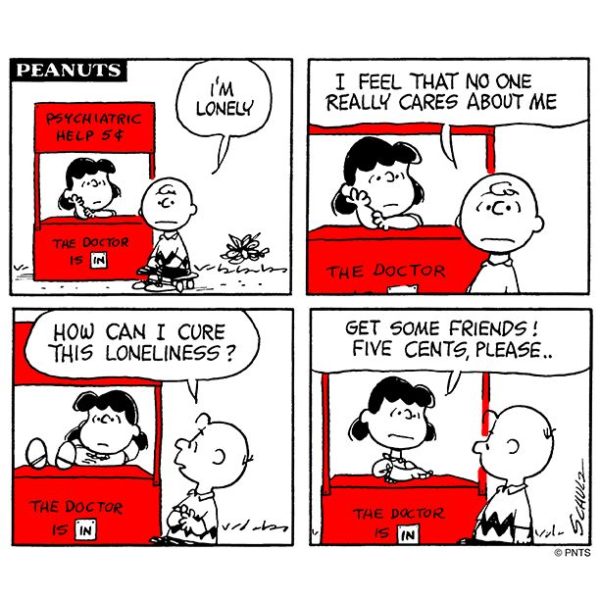

Among other things, aid work is a place of learning, new friendships, of personal and professional growth. It can also be a lonely place, in the field and back home. Once the excitement of a new post begins to fade, a sense of isolation may creep in. If you feel lonely, fear not, you are not alone! It is not unusual to feel that beyond work there’s not much else to do in “the field”, maybe some expats’ gathering here and there, lots of alcohol, same conversations heard before, same faces that show up every time there’s free booze. An aid worker told me how lonely she felt at those aid workers’ parties. I often felt the same myself: a bunch of grown ups, pretending to be in Neverland, while it’s actually Afghanistan or Iraq. Beyond burnout, what’s real in the field is boredom, and to fill up that void you work all hours or hang out at UN parties “trying to have fun.”

No matter how motivated you are, how do you “prepare” for that sense of loneliness and boredom that comes from being in a challenging place, sometimes on lock-down, with lots of time on you hands? Pretty much the only preparation I had before my first mission was: bring lots of films and books (don’t count on streaming). I would add: bring tons of patience, you will need it, with yourself and with others. And make sure you keep up with life beyond aid work and keep connections with home – however you define that – alive.

Back Home

Your time away is up: months flew by, you have learnt to enjoy those moments of solitude in the field and have build new friendships and connections. But alas, it’s time to leave. Home will provide a well deserved rest and for sure friends and family can’t wait to hear about the amazing work you’ve done. Aid work provides such incredible stories after all, no? (No, it doesn’t, at least not in the “entertainment” sense of the word, unless you are Sean Penn).

Your time away is up: months flew by, you have learnt to enjoy those moments of solitude in the field and have build new friendships and connections. But alas, it’s time to leave. Home will provide a well deserved rest and for sure friends and family can’t wait to hear about the amazing work you’ve done. Aid work provides such incredible stories after all, no? (No, it doesn’t, at least not in the “entertainment” sense of the word, unless you are Sean Penn).

Home – that’s where it can get tougher: the loneliness that creeps in once aid workers return from the field is baffling. A quick debriefing and most people are on their own until the next deployment. The reverse culture-shock is harsh to digest: loved ones don’t understand what you actually do for a living, they can hardly place Sudan, Afghanistan, Gaza on a map, and some seem to have the most racist ideas when it comes to welcoming refugees. How can they possibly engage in some meaningful way with what you’ve been through? They’ll happily listen to a few anecdotes and then is back to the latest TV series (the one you’ve never heard of), back to who’s dating who, who’s pregnant, who just had a baby – John has a new job, Mary bought a house, etc. Back to the day-to-day business that leaves you feeling like an alien in your own country.

Plus now your daily life lacks the structure and routine that you had in the field. You’re not sure how long you’ll be back for – after all staying at your parents’ age 40+ is not ideal – so you’re not committing to anything that requires you to stick around. Suddenly you can’t take that loneliness and sense of alienation any more. You’re off to Iraq. Better the devil you know.

(The “antidote” to loneliness? Mine is learning to enjoy solitude)

***

What to read:

For the action-type: If you haven’t read it go for the Millenium Trilogy – 3 (actually 4) volumes that will make it easy to avoid any UN party in town.

For the more contemplative-type: Thomas Merton, Thoughts in Solitude

For the thinking-type (or if you don’t know where to start): How to be Alone