Aid workers on idealism and pragmatism, diversity and the challenge of having a ‘normal life’

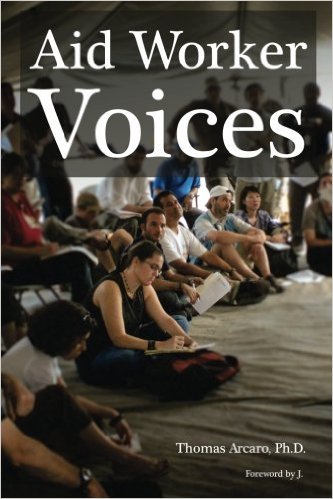

I’ve been reading Aid worker Voices by sociologist Tom Arcaro recently and I’d like to share some of its findings. As the title suggests aid and development professionals offered their views and opinions on a wide range of topics related to their experiences in the sector: the highs and lows of aid work beyond the false and romanticised image seen on the media. That’s why this is the sort of book that needs to be on every “wanna-be aid worker” reading list, and on the kindle of those new to the field.

With the help of veteran aid worker J., Aid worker Voices looks at a wide range of issues that touch the life of aid responders, from the personal to the professional. I picked three important issues that can offer insight to both young and seasoned aid workers:

1.The transition from idealism to pragmatism

2.LGBTQ aid workers: ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’

3.The challenge of having a ‘normal life’: The story of Becca, aid worker in her mid-30s

From idealism to pragmatism

In the vast majority of cases aid workers start out as idealists. I think this is beautiful and necessary. But of course there is a risk: when we see the reality of the job, cynicism and a cold form of pragmatism can kick in as a form of self-defence. The phrase by stand-up comedian George Carlin “scratch any cynic and you will find a disappointed idealist” often applies well in the sector. Here are two voices from Arcaro’s book that illustrate how the field can (re)-shape us:

“Salary and Benefits. Though no longer idealistic […] I don’t see the aid industry as being any worse (or better) than anything else out there. It’s still more interesting than working at A-1 Insurance Company and more sophisticated than being a high school teacher…you do still get to travel and see and learn things most other careers do not afford you. Finally, expat colleagues are really great even when annoying. You can’t really go back. Besides, not sure what else I would do at this point. Yes, reasons are very different. But I’ve learned to accept a different narrative so it makes it ok.”

“I believe in solidarity and mutual aid; whenever possible, elevate and act on the priorities and needs of people advocating for themselves, for example in justice- oriented social movements. I do aid work for my job because it’s a way to offer help and resources at the moment when people most need it, with (I believe) less harmful impacts than ‘development’ that’s done without the active centering of social movements. The rest of my (nonworking) life is devoted to organizing and solidarity activism. Aid work is my compromise: I get paid, I get to help, I get to learn first-hand what is going on and how, and I get to feed my cowboy streak without buying too deeply into a development project that dictates long-term distribution of resources according to funder pleasure.”

The journey from idealism to pragmatism is not just a personal one, it invests the institutions we work for. The next topic where ideals and reality often clash is inclusiveness and diversity.

LGBTQ professionals: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”

A while back I read an academic paper titled “There Aren’t Any Gays Here”: Encountering Heteroprofessionalism in an International Development Workplace. I love the title, because it gives a clue into the lies we still tell about certain institutions like the army, the church…and aid organisations. My guess is that “it looks like there aren’t any gays in aid” due to a mix of ‘macho mentality’ and protection. In fact, while the former is becoming less and less popular (but still alive and kicking), the reality is that in many countries where aid workers operate, it’s safe for staff to keep a low-profile on LGBT rights both inside and outside the office. Tom Arcaro’s book gives aid workers a platform to come out, so I picked a couple of quotes to exemplify how the sector deals (or not) with LGBT issues:

“As an industry there is very limited recognition of LGBTI staff and/or how their security, health and well-being might be affected by their identity and orientation. So, although many individuals who work in this industry are accepting, the industry as a system is not.”

“While the AID industry in certain ways can be quite progressive in certain ways, it also continues to perpetrate a lot of the same problems that underscore homophobia within our global discourse. It silences LGBTI staff versus raising their profiles or supporting the issues. They fail to understand the complexities of why Gender and sexual diversity issues, just like gender, underscores all development issues beyond just staff.”

If LGBT staff face challenges, women get their share too in a sector that seem to survive on the constant turnover of the “forever young, forever single and forever on the move.”

The challenge of having a ‘normal life’: The story of Becca, aid worker in her mid-30s

This is my favourite part of the book, a snapshot of life in the field, highlighting the good and bad, the enriching and ‘traumatising’ experiences of aid with a bitter-sweet conclusion: after (not so many) years in the sector, it becomes difficult to appreciate what ‘having a normal life/job’ means:

“But the thing about aid work that they don’t tell you … you can’t un-see what you’ve seen, good or bad. I can’t un-see or un-experience the amazing days I spent at the beach on the South China Sea in Vietnam any more than I can un-see or un-experience working in an HIV orphanage in Uganda. And the truth is, I don’t want to – all of those experiences have made me who I am, and I think my life is enriched for them. Sure, they’re difficult to explain to folks that haven’t seen/done things along a similar vein, but … they’re part of my story – and I think it’s a story worth telling.

While my career is in a pretty good place, I’d say my relationship life is … meh. I have great friends and a supportive family, but … I’m the only one in my group of friends that is unmarried and without kids. I’m currently single (and ready to mingle, fellas!), but tend to work a godawful number of hours in a week, travel frequently, and spend any free time I carve out sleeping, or binge watching Netflix, or traveling domestically to see friends and family, or hanging out with my dog. I’ve recently realized that I live for my job, as opposed to the other – “normal” – way around.”

Aid Worker Voices is an essential read for those who are considering a career in aid, and for anyone who wants to understand the everyday life of an aid worker with its frustrations, dilemmas and joys.

***

About the book and the author:

In 2014, a sociologist from Elon University and professional humanitarian teamed up to study the aid industry. Through a census-style online survey that was among the first of its kind, over 1,000 aid and development professionals shared their views and opinions on a wide range of topics related to their experiences as the core of the aid industry’s workforce. This book is the analysis of those 1,000+ responses. As the title suggests, this represents the voices of humanitarian aid and development workers around the globe – a diverse array of individuals with deep, intense and equally diverse feelings on what it means to be part of today’s humanitarian workforce. Essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the global aid and development industry better. All net proceeds from this book will support the Periclean Scholars at Elon University and the Periclean Foundation (Source: Amazon.com)