This post is part of Aid to Zen – A Quick Guide to Surviving Aid Work from A to Z by Alessandra Pigni.

***

“An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior” wrote psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl. At a time where we are invited to overcome suffering with the power of positive thinking, I like to remind myself and my fellow aid workers that while our mental attitude matters, mourning a loss, grieving following a traumatic event, crying and having what may be considered an “abnormal reaction”, can indeed be a sign of humanity and a mark of sanity. Going numb and ending up with no more compassion in the face of the suffering of others, as well as our own, is somewhat more worrying.

Traumatic events can lead to a breakdown of our life. Sure, they can make us stronger, but they can also destroy us. Building the courage and strength to find meaning in deep suffering doesn’t necessarily happen straight away. For some of us the traumatic event is so shattering that it leads to a dramatic upset of our everyday life by disrupting sleep, work and personal relations, leading to fear, panic, anger, a sense of hopelessness. That’s when the label post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comes along. In the face of challenging experiences that aid workers face (kidnapping, war, natural disasters, witnessing violence, but also, divorce, illness, death of loved ones), a first and fundamental step is to acknowledge the suffering, and sometimes literally “sit” with the suffering. It’s not a recipe for happiness, it’s just a tried and tested method that helps many, including myself.

Zen master Thich Nhat Han writes that when animals are wounded they retreat in the forest and tend to their wounds:

“Animals […] when they get wounded, ill or overtired, they know what to do. They find a quiet place and lie down to rest. They don’t go chasing after food or other animals — they just rest. After some days of resting quietly, they are healed and they resume their activities.”

Often times the healing begins with tending to the wound (“trauma” means “wound”), not with wanting to make sense of it straight away. Trying too hard to find meaning in a traumatic event may only lead to a sense of guilt and shame if we are unable to bear the burden with a smile and grow from it.

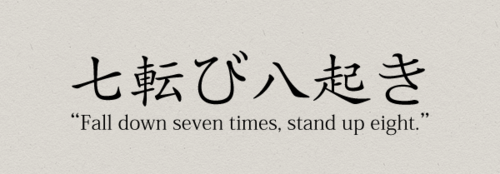

We can overcome trauma and grow from and through it, only if we accept that first there is a time cry, a time to retreat like a wounded animal. Those who jump too quickly to a “think positive” attitude, miss the fundamental “step” that requires that we grieve over a loss.

Post-traumatic stress disorder does not have to be the end result of a traumatic event, but the thought that we can quickly go from trauma to personal growth is naive and places a huge burden on the shoulders of those who are suffering. Post-traumatic growth – a helpful concept introduced by clinical researchers in the 1990s to illustrate how trauma can sometimes be the springboard to greater well-being – is a process and a journey, not a step in a behavioural manual.

The dark night of the soul cannot be avoided with positive thinking, but it can be overcome by giving ourselves the time to grieve, knowing that we may one day discover meaning in what today seems cruel and meaningless. Maybe we need to consider that post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth are part of the same journey because “when we are no longer able to change a situation” wrote Viktor E. Frankl “we are challenged to change ourselves.”

***

What to read:

Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning