This post is part of Aid to Zen – A Quick Guide to Surviving Aid Work from A to Z by Alessandra Pigni.

***

“The power to help is just about as dangerous as hard power” – Binyavanga Wainaina

Those who are fairly new to the aid blogosphere have missed out on one of my favourite do-gooders’ blogs. Good Intentions are not Enough run roughly between 2009 and 2013, thanks to the labour of love of Saundra Schimmelpfennig. Her insights and research gave many of us critical thinkers food for thought.

With thoughtful arguments, without moralism and without falling prey to the aid worker’s most dreaded companion – cynicism – Saundra covered the ethical side of aid. When it wasn’t cool to talk about the misuse of poverty to raise funds, she did it. When it wasn’t fashionable to write critically about in-kind donations, she did it. When it wasn’t hot to analyse the pros and cons of voluntourism she did it. When it wasn’t hip to disclose one’s own burnout, she did it. Eventually, tired of shouting into the wind, she moved on to other shores. Now that criticizing aid right and left is a trendy hashtag, I utterly miss her intelligent and deep analysis.

Luckily the content of her blog has been kept alive by USAID (I know…). I invite younger generations to learn as much as possible from it, and older generations maybe to unlearn poor common practices adopted in the field and rethink some aspects of the aid paradigm. Because no matter how well we know that good intentions are not enough, I still hear aid workers falling back on the poor argument that “doing something is better that doing nothing”. Indeed for ourselves being in “the field” is sometimes better than sitting at home. But aid is not a form of entertainment, it’s not a lab to train our skills, it is not a form of therapy for misfits, nor is it a way to escape life back home.

Luckily the content of her blog has been kept alive by USAID (I know…). I invite younger generations to learn as much as possible from it, and older generations maybe to unlearn poor common practices adopted in the field and rethink some aspects of the aid paradigm. Because no matter how well we know that good intentions are not enough, I still hear aid workers falling back on the poor argument that “doing something is better that doing nothing”. Indeed for ourselves being in “the field” is sometimes better than sitting at home. But aid is not a form of entertainment, it’s not a lab to train our skills, it is not a form of therapy for misfits, nor is it a way to escape life back home.

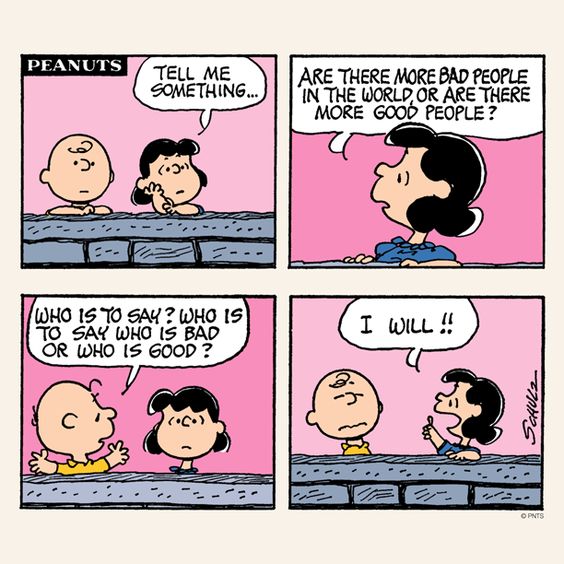

When we land in “the field” as “whites in shining armor” – meaning well and without a clue – we run the risk of doing more harm than good. “The White Savior Industrial Complex is not about justice” writes Nigerian-American author Teju Cole, “it is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege”. Yes, that need for a big emotional experience is responsible for many humanitarian careers (and here I include fellow war reporters, photojournalists and the like). Our own ambition (and confusion) combined with the power to help, can be as dangerous as hard power.

From our private life, to our professional life, still too often we burden people with our own need to be good, leaving others with the unintended consequences of our good intentions. “Saving others” at all costs, becomes a way to make sense of our life. Reflecting on our own ambition “to do good” does not mean advocating for indifference. It’s more about engaging in a dialogue where so-called “people in need” are given a chance to say “yes, please” or “no, thank you”. If you have ever been in need yourself, you will know that keeping your free choice, means keeping your dignity, which goes hand in had with keeping your sanity and wellbeing.

***

What to read:

Mohamed Cherkaoui, Good Intentions. Max Weber and the Paradox of Unintended Consequences

Listen to: Binyavanga Wainaina — The Ethics of Aid: One Kenyan’s Perspective (Aug 27, 2009)