This post is part of Aid to Zen – A Quick Guide to Surviving Aid Work from A to Z by Alessandra Pigni.

Much has been written about the myth of the field and fieldwork. There are countless memoirs about life in the field with its ups and down, lessons learned, lessons forgotten. I won’t repeat what’s been said already. I just thought I’d offer my very personal take on “the field” and what it does to us from a psychological angle.

The field is a pretty interesting place for aid workers, and one that can turn each and every one of us into a better or worse version of our “home” selves.

The field is a bit like a college town for grown-ups: in spite of the strict rules, up to a point anything goes. It’s a place where we can express sides of us that do not fit our home persona, because as an aid worker told me “what happens in the field…stays in the field”. Scary, if you think about it. Liberating, if you think about it again. Two sides of the field coin.

Take the person who is prone to drinking a bit. Well, give it a few months in the field and John may develop a full on drinking problem. But fear not, he will still be seen as fully functional by fellow aid workers. After all booze is part of the lifestyle.

Take the person who is prone to drinking a bit. Well, give it a few months in the field and John may develop a full on drinking problem. But fear not, he will still be seen as fully functional by fellow aid workers. After all booze is part of the lifestyle.

A social smoker? It may not be before too long that Mary finds herself chain-smoking. More than one aid worker confessed: “In the field I go back to a pack a day.”

Prone to anger? The field will test your patience to the limit. I’ve heard (and witnessed) countless embarrassing stories of managers losing it and staff ripped to pieces by grown-ups unable to manage their emotions.

Selfless and generous? If the field does not turn our idealism into cynicism, we may flourish into a more compassionate and empathic human being. Sadly it’s not often the case.

A gifted leader? A few months in a mission may well strengthen our vision and ability to lead others…or we may succumb under the bureaucracy of aid. Take your pick.

Even though life in the “field” looks more like spending lots of time an office, than engaging with hosting communities, we perceive it as adventurous and far from office work, no matter how many hours we spend behind a desk, glued to a screen.

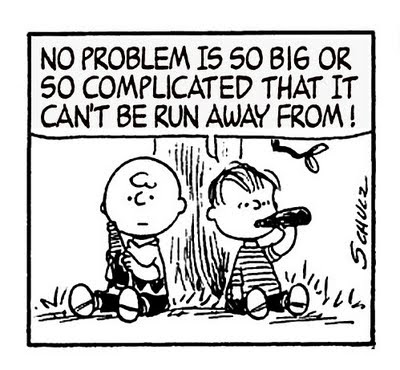

Whatever it may be, aid workers seem to believe that “the field” gives them an aura of coolness. What I’ve experienced is that it amplifies our traits and behaviours, the good and the bad. Unless we find our own personal balance within – I know a couple of aid workers who have – the field is an addictive business where we can end up doing more harm than good, to ourselves and to others.

A word of advice: love the field, and find a place to call home.

***

Film to watch: A Perfect day